By Stuart Theobald

Why invest only for financial gain, when your investment can also have positive social consequences? The idea that our investments can do good in the world, rather than just serve our narrow financial objectives, has excited a new generation of savers. But is impact investing just a fad, or a deeper shift in the mechanics of the investment market? I think it can be the latter, but we must avoid wishful thinking and confront some of the challenges to effective impact investing.

What is impact investing?

There are various definitions. A useful one comes from the Global Impact Investing Network: “The intention to generate social and environmental impact alongside a financial return”. This definition excludes some related ideas such as socially responsible investing (SRI). SRI works by filtering portfolios, either negatively to exclude companies deemed to be harming a particular social objective (for instance, coal mining), or positively by directing investment into companies deemed to have a positive impact on particular social objectives (for instance, renewable energy). Impact investing, in contrast, is focused on investments that are designed to have a particular impact, for example, shares in a company that has set employment creation as a specific goal, or one focused on technology to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. One exciting example of impact investment is the social impact bond. A variety of this has been pioneered in the Western Cape to target early childhood development outcomes, in which NGOs are directed to achieve targets and investors receive a payoff if they succeed. But, as I will discuss, there are many other types of instruments that qualify.

Types of impact investors

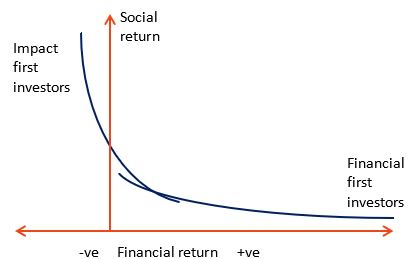

All investors have unique objectives. That’s true in impact investing too. The first way to split impact investors is in the balance between financial gain and social impact. The interests of investors can be placed on a continuum – from those who are “financial first” to those who are “impact first”. Different investors sit at different ends of this continuum. At one extreme, investors argue that impact investing is a way to earn superior returns to market returns. They argue that investing which advances the interests of society is more likely to earn high and sustainable profits. I don’t think this is a coherent proposition – conceptually, any company can increase social returns further by directing profits into social outcomes. It is not true that greater social outcomes will lead to greater profitability, at least in general. At another extreme, investors are willing to lose their capital entirely providing certain social objectives are achieved. We can analyse the trade-offs between these two objectives. Social outcomes can be cast in terms of social utility created, whereas financial outcomes can be treated in the usual sense of returns.

This is illustrated in the graphic above which shows indifference curves for two types of investors. The lines represent points along the balance between social and financial returns that the two different types of investors will accept. Impact first investors are willing to accept a negative financial return if the social return is high. In contrast, financial first investors will accept low social returns in return for high financial returns. This analysis suggests there is an opportunity to meet the objectives of both types of investors, where the two indifference curves cross, which would be an impact investment that balances social and financial returns at just the right level to satisfy both financial first and impact first investors. An investment product that pitches at this point is likely to find the greatest demand in the market.

This makes it seem that there is a magical point at which all impact investors will get what they want. But that is likely to be illusory.

Conflicts of interest

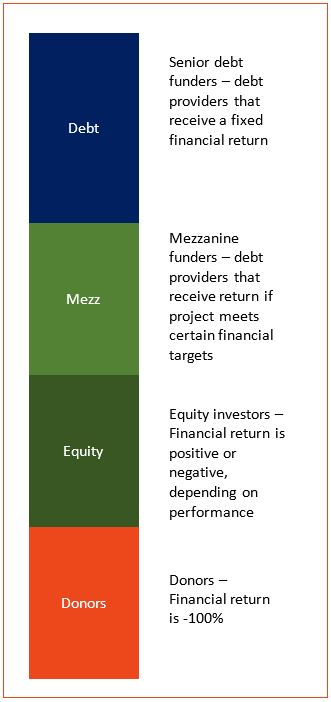

Projects that are designed as impact investment projects often draw funding from multiple types of investors, all of whom could be interested in impact investing. However, differences between these investors can lead to conflicts of interest.

Consider a waterfall of different forms of investment in a potential social impact project (shown in the graphic alongside). This kind of capital structure would work for several types of project such as schools, hospitals or employment-generating factories.

At the different extremes of this cascade you have donors and debt providers. Donors do not expect any financial return, in fact the money they contribute will never be returned. At the other extreme, debt providers are usually using the money of depositors or low risk investors such as pensioners and require fixed returns in the form of interest.

As a project is implemented and intended outcomes are not achieved, the strategy has to be amended. A donor would insist that the social objectives are given priority, whereas a lender would insist that the financial objectives are given priority. Indeed, one can imagine a scenario where in the case of weak financial performance, the donor’s money is being used to pay interest to the lender rather than on social outcomes.

There are some potential institutional structures that can deal with these conflicts. Some include:

Focus: Only use one type of financial instrument, for example, donor grants.

Satellite model: Ring fence donors in one entity responsible for one outcome, with other forms of capital in a separate entity that provides complementary services.

Financing lifecycle: Use donors for the initial phase, for example during setup or to fund research and development. Different funders are introduced at the point of scaling up the project.

In addition to the conflicts between funders, there are potential conflicts between managers and funders. Managers may have different priorities and have an interest in ensuring the financial sustainability of the project. If financial returns are under pressure, they may well prioritise efforts on financial returns rather than social returns.

Monitoring

It should be clear from these considerations that one of the important issues in impact investing is measuring the social returns. Financial returns are comparatively easy to determine and there is a well-established institutional structure, from auditors to financial markets, to monitor financial performance. It is much less clear how social returns should be determined. This is a lively area of debate in academic and practice circles and there are many ideas on how social returns can be measured. In some cases, very simple measures are effective – for example, specific health indicators can be used in the case of early childhood development. But many projects have less tangible and difficult to measure outcomes. They also have to be guarded against manipulation to ensure that any measures are appropriate and independent. Projects must ensure that they signal their social returns to stakeholders. Investors must monitor and evaluate impact. These create a residual loss to both social and financial returns as monitoring costs have to be incurred. Effective evaluation and monitoring is essential for impact investing to be a credible alternative. I think it is also important that investors themselves have access to information to assess effectiveness directly – the disciplinary effect of investors seeking to maximise social impact is important to drive innovation.

Who should be impact investing?

Any investor might be interested, though currently regulation would be an obstacle in some cases, such as pension funds, when it comes to more innovative structures. One clear investor type that would suit an impact strategy is foundations. These usually have an endowment, such as a portfolio of assets, that generates returns which are then used to fund philanthropic activity. There are several examples in South Africa of family foundations (like the DG Murray Trust), black empowerment foundations (like the FirstRand Empowerment Foundation) and renewable energy project-funded community foundations. While these can have restrictions on what they can do with their portfolios, for instance, requirements to remain invested in legacy instruments, there are opportunities to use their portfolios to add to the impact that grant making supports. For instance, a foundation can invest in education-focused impact investing as part of its asset portfolio, in addition to making grants that support educational outcomes. To my mind, foundation portfolios should all be considering how impact investments can be included within an overall investment policy, which can additionally include socially responsible investing screens.

But it should not stop there. Some asset managers (for example, Ashburton) offer impact investing funds that any member of the public can invest in. In due course, policy changes may allow for more institutional money, such as pension funds and insurance companies, to be directed into impact investing funds. Already some of this money can find its way into impact instruments that are structured appropriately.

Role in South Africa

In South Africa there is a growing political debate about access to private capital to achieve certain public ends. One example is the issue of prescribed assets, which the ANC has announced in its election manifesto that it intends to investigate. Under a prescribed assets regime, institutional investors are forced to invest in certain designated instruments, usually a variety of government bond. This approach is rare internationally, with the Apartheid state among the only in history to use it. My view is that prescribed assets is a very harmful policy as it distorts markets and blunts the disciplinary effect that investors should be able to have through their choice of investments. Imagine how much worse the state capture era might have been if investors had been compelled to invest in SOE bonds…

Impact investment, in contrast, could play a more positive role. Such investments can include those pursuing defined public benefit objectives such as education or healthcare. As a matter of public policy, we are comfortable allowing tax deductions for donations to organisations that support public benefit activities, so the idea of defining such objectives is well established. We are also comfortable with the fact that individual choice dictates which particular organisations end up being supported. Public policy could encourage impact investment by allowing institutional funds to direct a tranche to it, as they currently do with hedge funds. It could also be earmarked for favourable tax treatment, for example by allowing impact funds to be included in tax free savings accounts for individuals.

Impact investing is not a panacea – to really address unemployment and inequality we need broad economic development far beyond what impact investing can achieve. But it can make a difference on the margin and with certain problems that are hard to solve through traditional investment or public spending. For those reasons, it should be encouraged.