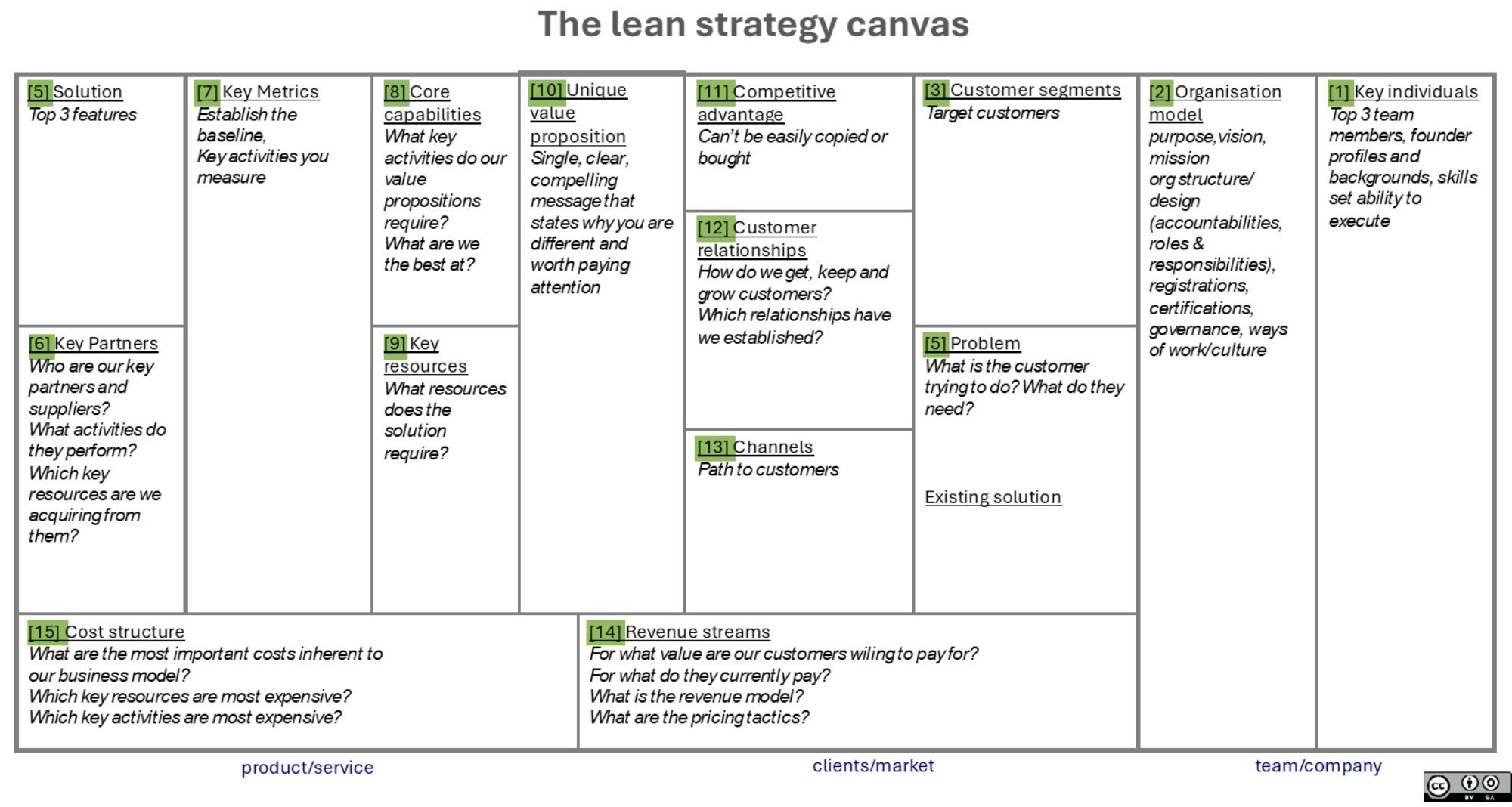

A canvas is a single sheet to map your business strategy and helps you go from idea to implementation by identifying the key risks in your concept. This is an action-oriented, assumption-busting approach to crafting evidence-based strategies that work. Following in the tradition of business canvases and lean startup methods, I’ve added venture capital ideas and some post-structural theory to diagnose and solve strategic challenges in businesses – big and small.

This is the lean strategy canvas. It can literally show your entire business strategy on one page. You no longer need to spend endless hours writing a long business plan and creating complex financial models before you even know if you have a real business opportunity. Using a canvas and its underlying evidence-focused method gets right to the main assumptions and risks in any business idea.

The way to use the canvas is simple:

- Start by writing down all the answers to the guiding questions and text in each block. Follow the numbers from 1 to 15.

- Review the evidence for each of the statements in the block. Immediately, the assumptions without evidence will become apparent. These are also the main risks in the model.

- Find the evidence or mitigations for the assumptions and risks.

- Pivot if necessary.

- Progress the model until all parts of the canvas “turn green”.

I won’t spend too much time repeating the focus of the blocks created by Osterwalder & Pigneur or Maurya, or the Kupor approach to VC decision-making. Their contributions are much deeper than I can repeat here and are best explored in their original texts.

It’s this core of agile methodology and customer development that are worth underlining. This perspective is critical for the canvas(es) including my own iteration. Three principles are key

- Building the canvas (and ultimately the business model) is done in sequential steps informed by agile methods. The steps include plan, design, develop, test, deploy and review in a constant cycle until a working product is delivered to clients and even beyond that for constant improvement as needs and demands change.

- Getting out of the office to talk to customers. This is essential in using the canvas and the core idea of talking to potential stakeholders (customers, suppliers, collaborators, and so on) can be applied throughout the process. It simply urges the user to find the evidence for anything that is written in the canvas. I call it “turning the block green” indicating that until the user has evidence, that block remains “red or orange”. Only evidence and data can support or refute the assumptions, risks and claims embedded in the canvas.

- Identifying key risks and assumptions: the canvas remains just a set of ideas until the evidence is found to support them. The canvas can easily draw attention to the main risks in the model. It’s these risks that the user has to address, mitigate or pivot on.

One important aspect about this outreach to customers is not about selling anything (yet). The first step is a about learning as much as you can about customers. Go with a curious mind, a beginner’s mind. Do some background research on the business, and the key people. Go and listen. Ask what their challenges are and offer ways to solve them. Co-create with them. What are they concerned about? Do you have a solution to their problem?

Background and influences

The name “lean strategy canvas” should ring some bells. Maybe you’ve heard of the “business model canvas” from Business Model Generation by Alexander Osterwalder & Yves Pigneur (2010) or The Lean Startup by Eric Ries (2011). Or even Running Lean by Ash Maurya (2013). These aren’t the only authors working on ways of enabling startups and scale-up -businesses and there have even been applications of lean principles to non-profits like Lean Impact by Ann Mei Chang (2018).

The genesis of the movement is Steve Blank, a professor of entrepreneurship at Stanford University. In 2006, he published The Four Steps to the Epiphany: Successful Strategies for Products that Win, which brought the idea of customer development into view. Simply, customer development emhasises the need to talk to customers to find out if the product would meet their needs. Even Blank drew on the principles of agile software engineering, which in turn drew on the agile supply chain approach famously used by Toyota to drive efficient, on-time, on-demand availability of parts in manufacturing.

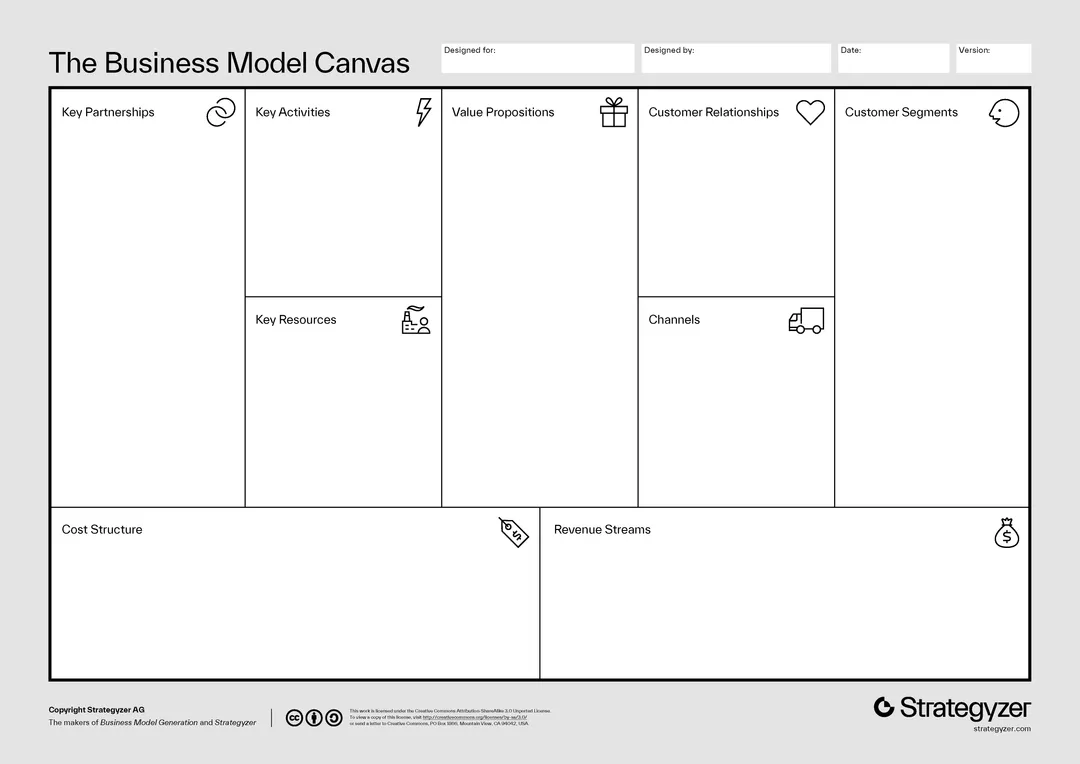

The business model canvas

Below is the OG – the original business model canvas created by Osterwalder & Pigneur in 2010. It’s a revelation, a thing of beauty.

The power of the canvas lies in its simplicity. The notion that a strategy or business plan could be represented in just one sheet was compelling. I was introduced to it by a colleague in Standard Bank where I was entrusted with creating a commercial model for enterprise development in the business banking division. Ours was intended to be a for-profit offering, that would package the bank’s services in a special format for enterprises in corporate value chains (including suppliers, distribution partners, franchisees and customers).

The original creators licensed the canvas under [Creative Commons BY-SA]. This designation allows for the distribution, remixing, adaptation and building upon the material in any medium or format, so long as attribution is given to the creator. This license allows for commercial use. It also requires that any work added to the original be licensed under the same terms. I acknowledge the original creators, the subsequent remixers, and now offer my own contribution on the same terms.

Adding Maurya’s ‘Problem, Solution, Key Metrics, Unfair advantage’

Then I discovered Ash Maurya’s contribution to the canvas through his book, “Running Lean” from 2013. Maurya made a few adaptations that he outlines in blog post: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/why-lean-canvas-vs-business-model-ash-maurya/, stating that while he found the book useful, it was more focused on showing the business model of existing businesses, rather than showing what got them there. He added Problem, Solution, Key Metrics, Unfair advantage and removed key activities, key resources, customer relationships and key partners. I added Maurya’s new categories to the original canvas.

Adding Kupor’s “Key individuals”

The next influence on my canvas is from the work of Scott Kupor as detailed in his book: “The secrets of Sandhill Road”. Kupor is managing partner at Andresen- a VC based in Silicon Valley, on Sand Hill Road. In the book, Kupor describes the key elements that investors look for when evaluating startups for VC investment. He indicates that the main factor for VCs is the team or the key individuals. They have to meet these criteria:

- Can they sell the vision?

- Are their credentials convincing and aligned to their business/product?

- What makes this team special enough to disregard others (with similar ideas, which are often not unique)?

- Is the founder doggedly focused on the goals and unreasonably resilient?

Later, this category was expanded to cater for existing businesses that have a larger people structure to show job accountabilities, roles and responsibilities of key individuals.

Adding “Organisational model”

When I started using the canvas to analyse non-profits in South Africa, it became immediately apparent that the canvas was missing a block to capture the organisational form. In that country foundations can be NPOs, PBO and trusts. All three have unique legal and tax structures, so clarity on their registration was necessary. This element was also useful when I applied the canvas to analyse complex commercial enterprises that had subsidiaries. This category has subsequently evolved to include the vision, mission and purpose, operating model, culture and ways of work.

Grounded in Foucault’s theories of social order

I would be remiss if I didn’t acknowledge the influence of Michel Foucault on my interest in the canvas. I worked on my PhD between 2010 and 2015, and adapted Foucault’s theories to financial services strategies for financial inclusion. Foucault was a French philosopher known for his radical critiques of social disciplinary technologies. An example is his emphasis on the importance of deconstructing language for its role in creating reality. His work is dense, and I’ll only mention one aspect which is that he draws attention to how we construct roles for people. Applied to strategy, I draw on this insight to question my own ideas about people and their needs. A great example from my own experience is the idea of the unbanked that I encountered in building banking services for the economically excluded majority of South Africans. Instead of thinking of people who don’t use banks as unbanked, it would be better to think of them as enmeshed in an economic system that does not conform to our narrow conception. Personally, this deconstruction of my perceptions remains one of my biggest lessons in building successful business strategies and deeply informs my work on the lean strategy canvas.

Why do we need lean strategy?

Doing strategy in business can be expensive. Getting it wrong, can be existentially consequential. How do we make strategy easy, accessible? How do we make it more accurate? Enter lean strategy. This approach to strategy draws on developments in software engineering and project management that have been transformed by agile methodologies. Perhaps it is inevitable that agile and lean methods are now infiltrating the core of business. Information technologies digital transformation of back office processes and increasingly front-end customer engagement are both now often highly digital.

Engineers are no longer concerned with whether they can build digital infrastructures, but rather, the question to business executives is “should it be built?” This simple question gets to the heart of the matter, and it’s where strategy comes in. Should the business pursue this client segment or that one? How does it intend to provide highly valued, competitor-beating, customer-delighting products and services?

In my view, businesses exist to create shareholder value. To be clear, it’s not to maximise shareholder value at the expense of other stakeholders, such as clients, suppliers, partners, employees and the community in which it operates. One way to measure value for shareholders is profit–the surplus money that is left when costs are deducted from revenues. Importantly, value for shareholders is created by the business delivering value for customers.

By way of analogy, the profit is like a score in a football game. The score is not the game. It is simply a measure of how well one team is playing against another. In the same way, profit tells us how well the business is doing. If profit is the “score” of a business, then what is the game?

The game is what employees of the business are doing to generate the profit. Unlike a sports game, businesses are complex, with many activities taking place across space and time. You can’t just turn on the TV and watch the game, so how can we find a way to see the game we play in business? Afterall the coach needs to watch the game to see what the players are doing–both good and bad–to generate the score.

I propose to watch the game of business through the lean strategy canvas lens.

A brief personal biography

Why should you believe me? Over many decades, I’ve been fascinated by information and communications technologies. This interest evolved to now working at the intersection of these technologies and business strategy.

- Around the age of 10, while my father was doing a bachelor’s degree in computer science, I used his text book on GW-BASIC – programming language developed by Microsoft- to create an interactive weekly TV guide by adapting a set of code to this purpose.

- My first career path was in the application of web technologies to media at the Sunday Times and Carte Blanche – two of South Africa’s premier weekly news journalism services.

- In my 20s, I was a volunteer at the Joburg Computer Clubhouse – an after-school learning programme for children from under-resourced schools using state-of-the-art computers and software in an exploratory way rather than for pedagogical purposes. As a volunteer mentor, my job was not to teach but to respond and guide.

- My MSc in New Media, Information and Society at the London School of Economics was a joint offering between the Media and Information Systems departments and deepened my appreciation for the philosophical and sociological dimensions of technologies. In my thesis, I explored how innovative technologies can be used for economic development in Gauteng–the most vibrant economic hub in the country.

- My MBA thesis was on how strategy happens in Vodacom–an industrial-scale mobile telecommunications company. I worked there at the time as senior product manager focused on commercialising new technologies for mobile advertising.

- Later I joined Standard Bank to help build banking services for the ‘unbanked’ using mobile phone technologies.

- My PhD research between 2010 and 2015 went further to explore specific aspects of mobile technology in the context of financial services firms’ strategies for financial inclusion.

- In 2017, I was certified as a Scrum Product Owner.

- My professional work is now commercial research, a form of advisory service in R&D. I find opportunities for growth and expansion that are sustainable, innovative and deliver value for all stakeholders by leveraging information technologies.

Your feedback

In the spirit of agile and lean, I’d like to invite your feedback to improve the “lean strategy canvas”. The MVP is out there now, and as you use it, you may have ideas for how to improve it. I welcome your feedback: [email protected].