May 2017

By Stuart Theobald

A version of this piece was published in Gradient, the magazine of Absa Investments, which can be downloaded here.

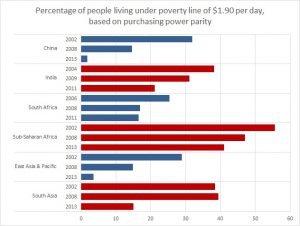

There is no doubt that economic growth is needed to reduce poverty. Those countries that have done it on a large scale have also had rapid GDP growth rates. That is particularly the case in South Asia where the proportion of people living in poverty fell from 29.4% in 2008 to 15.1% in 2013 . In East Asia and Pacific it fell from 14.9% to 3.5%. These were driven by high growth rates particularly in China, India and Vietnam.

But it was in Asia that concerns over the distribution of this growth first gained traction. The problem is that growth creates economic opportunities that are unevenly distributed. Those who are already wealthy or otherwise enfranchised are able to use their resources to take advantage of opportunities more quickly than those who are not. This is intuitively plausible: educated elites and established companies thrive in growing economies because they have the resources to pursue the opportunities that come with them.

For this reason, growth in Asia came with growing inequality. This is very difficult to measure – the statistics required have only recently begun to be collected in most developing countries. Data collected by Credit Suisse show that in India, for example, the richest 1% owned 36.8% of the country’s wealth in 2000, but in 2016 it was over 50%. Anecdotally, it was marginalised groups like lower castes, women and farmers who were said to be missing out. This may be because the opportunities were all clustered around services, which favours urban residents. This is not something rapidly developing countries are alone in experiencing: the US and Britain have shown the same trend of wealth moving to the top 1%. There are different reasons for this in the developed world, though more of them will apply in the developing world as it gets wealthier.

It is far from settled what the causes of growing inequality are, but it has coincided with a global structural shift of economic activity from resource extraction and manufacturing into services. In particular, low-skilled jobs in manufacturing were often relatively highly paid, but low skilled jobs in services are low paid possibly because it is much harder for labour to organise on scale in the services sector. Other social factors such as lower birth rates and increased participation of women in the workforce are contributors. That seems counterintuitive, but there is some evidence, particularly in the United States, that before the 1980s rich men tended to marry poor women, but now rich men and rich women tend to marry each other, such that inequality between households has increased. These factors are certainly having political consequences in the developed world, too, including Brexit and the election of Donald Trump. Developing countries can expect these factors to become increasingly relevant too.

According to Google Trends statistics, the term “inclusive growth” is overwhelmingly searched by Indian users – for every 100 searches since 2004, there are only four from the next biggest country, the US. In the 2009 Indian election, Manmohan Singh and the Congress Party campaigned on the basis of inclusive growth as a core policy, garnering enough votes to lead a coalition government. This was in response to accusations from the left that Congress had previously pursued “neo-liberal” policies. It again featured heavily in the 2014 election campaign of the Congress Party but this time the party lost to Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party. Since then, inclusive growth has become less of a headline-grabbing issue in India. The Singh campaign was occasionally vague on what it meant by the term, but did point to focused rural infrastructure development, investment in education and health and various schemes that specifically targeted the poor with economic resources. Its political traction was driven mostly by a sense of unfairness about the pattern of economic growth that had occurred in India. To be sure, absolute levels of poverty had fallen dramatically, but the benefits of growth had gone disproportionately to the already well-off.

The concept has been working its way into South African policy discussions for some time, particularly alongside complaints that growth under the Mbeki administration was “jobless” and therefore failed to deal with inequality. In the National Development Plan that was finally released in 2013, inclusive growth was mentioned only five times in 489 pages, with no major substantive discussion of what it meant. However, the NDP’s policy proposals broadly reflect objectives that cohere with the concept as it was developing elsewhere in the world, with the plan dominated by a theme of eliminating poverty and reducing inequality. In 2013, Treasury’s medium-term budget policy statement included a chapter headed “Securing inclusive growth”. There wasn’t any discussion of what this meant or how it should be measured, but the specific policy initiatives included mechanisms that redistributed development in favour of the poor, including health and education, while budgets related to infrastructure, jobs, local government and community development were boosted.

When it comes to definitions of inclusive growth, one of the best comes from the Asian Development Bank: growth with social equity. The idea is that policy should be focused on “pro-poor” growth. In a 2014 document it pointed to three policy pillars for inclusive growth:

1. High sustainable growth to create and expand opportunities

2. Broader access to these opportunities to ensure that members of society can participate in and benefit from the growth

3. Safety nets to prevent extreme deprivation

Pillar one is in common with older notions of economic growth, though it too can be skewed towards focusing on areas of particular deprivation. Pillar two and three put the “inclusive” into the concept. Clearly these pillars can be in tension with one another – for example, social safety nets come at the cost of alternatives such as infrastructure investment that could be more growth-enhancing. But this cost is seen as a price worth paying for inclusive growth.

In practice, policies are all about ensuring economic opportunities for the poor. This means heavy investment in vocational and technical training in poor communities, access to capital to start businesses, support for early childhood development, and efforts to include new entrants into the economy, be they start-up businesses or unskilled workers. While South Africa has attempted to implement some of these, such as the Expanded Public Works Programme which created many jobs in deprived areas, we have been very bad at driving education and training for the disenfranchised. This is a result of the broad dysfunction of the Sector Education and Training Authority system and the collapse of the artisanal schemes it was meant to replace. The effectiveness of government spending on schooling is also notoriously poor. In these cases the policy intentions clearly align with inclusive growth but the delivery falls far short. Black economic empowerment has attempted to force economic opportunities away from big established businesses and towards small businesses and black-owned businesses. This has had the most success and, alongside the rapid expansion in the size of the civil service, can be credited for the growth of the black middle class that has taken place.

The third pillar is perhaps where South Africa has been most effective. The social grants system has expanded rapidly to the point where around 19 million grants are paid every month to over 12-million people, making South Africa one of the biggest social welfare systems in the world. It heled reduce the poverty rate rapidly from 2006 to 2008, but has stagnated since. This safety net is only meant to be a safety net. It is to protect those who cannot find genuine economic opportunities. It does not in itself provide any way for people to add value to the economy, to access opportunities that should be provided by pillar two.

Recently, a new concept has blazed into the policy debate, that of radical economic transformation (RET). While some have dismissed it as “radical economic gibberish” and there have certainly not yet been any proper expositions of the concept, one can point to some reasons it has gripped the public imagination. Inclusive growth requires the first pillar: high growth. Without it, questions about the distribution of economic opportunity are moot. Given the poor growth environment in the Zuma era, debates about the distribution of opportunities are like arguing what you are going to do on a summer holiday you can’t afford. Inclusive growth is motivated by the sense of unfairness that arises when elites are seen to be grabbing opportunities. In the absence of growth, that sense of unfairness is focused on the distribution of economic resources, rather than opportunities. And given South Africa’s still skewed distribution in favour of whites, this easily takes on a racial tone.

The problem for RET is just what policy stance to take. If it is to be the forced expropriation of assets from the wealthy and redistribution to the poor, whether this is through nationalisation, wealth taxes or other means, the consequences will be big for economic growth. It will end foreign direct investment and collapse domestic confidence, leading to a huge slowdown in the economy. That will put an end to any possibility of inclusive growth. So while RET has been described by some, including minister of finance Malusi Gigaba, as inclusive growth by another name, it is probably better to see them as standing in fundamental tension. RET is better described as a process of redistribution of wealth, for which the cost is growth, inclusive or otherwise. And given that we do not yet know what the long-term outcome of such a process is, considering the examples of Zimbabwe and Venezuela, such a direction of policy is very dangerous.

The difficulty is how meet replace voters’ sense of unfairness with genuine hope of a solution. To accept inclusive growth rather than RET, they will need to be convinced the growth with deliver for them. The focus must not be on growth for its own sake, but on growth as a means of opportunity for the poor. To provide such an argument in a way that voters can put their faith in it will require great political leadership. And that, ultimately, is the critical enabler for inclusive growth.